Manyscientists say there is not enough evidence that Biogen’s aducanumab is an effective therapy forthe disease.

TheUS Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval yesterday of the first new drugfor Alzheimer’s disease in 18 years was welcomed by some people looking forhope against an intractable condition. But, for many researchers, it came as asurprise — and a disappointment.

Aducanumab— developed by biotechnology company Biogen in Cambridge, Massachusetts — is thefirst approved drug that attempts to treat a possible cause of theneurodegenerative disease, rather than just the symptoms. But the approval hassparked a contentious debate over whether the drug is effective. Many experts,including an independent panel of neurologists and biostatisticians, advisedthe FDA that clinical-trial data did not conclusively demonstrate thataducanumab could slow cognitive decline.

The FDA instead relied on an alternativemeasure of activity, which sets a dangerous precedent, some researchers warn.

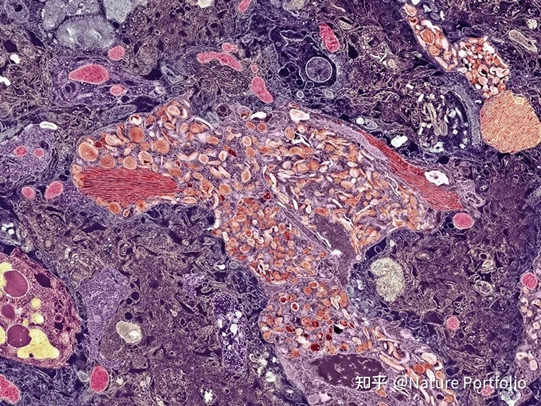

Plaques of amyloid-β in the brainare one target of Alzheimer’s disease treatments.Credit:Thomas Deerinck,NCMIR/SPL

Current Alzheimer’s drugs address onlydisease symptoms, for instance by delaying memory loss by a few months.Aducanumab clears out clumps of a protein in the brain called amyloid-β, whichsome researchers think is the root cause of Alzheimer’s. This theory is knownas the amyloid hypothesis. The FDA approved the drug on the basis of itsability to reduce the levels of these plaques in the brain.

“This is a very slender reed upon whichto hang an approval decision,” says Jason Karlawish, a geriatrician and co-director of thePenn Memory Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Despite the dominance of theamyloid hypothesis over the past few decades, evidence that links reductions inplaque levels to improvements in cognition is “thin, at best”, says Karlawish.

“Desperation should drive the funding ofscience, not drive the way we interpret the science,” he says.

Desperate need

But some patient groups are desperate foranything that might offset the effects of the incurable, progressive disease.Estimates suggest that 35 million people worldwide have Alzheimer’s.

“History has shown us that approvals ofthe first drug in a new category invigorate the field, increase investments innew treatments and encourage greater innovation,” said Maria Carrillo, chiefscience officer for the patient-advocacy group Alzheimer’s Association inChicago, Illinois, in a statement. “We are hopeful, and this is the beginning —both for this drug and for better treatments for Alzheimer’s.”

Others worry that the approval will havethe opposite effect — stymieing research efforts. Karlawishsuspects that people with Alzheimer’s might start dropping out of ongoingclinical trials to take aducanumab. Others worry that drug developers mightabandon other targets. If demonstrating that amyloid-lowering activity isenough to win regulatory approval, it might discourage developers from focusingon treatments with the big cognitive benefits that patients need, say somescientists.

“This is going to set the researchcommunity back 10–20 years,” says George Perry, a neurobiologist at theUniversity of Texas at San Antonio and a sceptic of the amyloid hypothesis.

‘Problematic data set’

Aducanumab, an intravenously infused antibody, isthe latest in a long line of therapeutic candidates that aims to tackle amyloidplaques. Although every drug of this type has so far failed to improvecognition, questions have persisted about whether amyloid-β is the right drugtarget, as well as whether researchers are testing the optimal therapeuticcandidates, the correct doses and the appropriate patients.

“The problem with most of the amyloidtrials is that they didn’t disprove anything,” says Bart De Strooper,director of the UK Dementia Research Institute in London. “They just provedthat a drug, in the way it was applied, didn’t work.”

Researchers’ concerns now centre on aducanumab’stumultuous passage through clinical trials and the resulting data set, which isincomplete and unpublished.

The FDA’s approval is based on data fromtwo phase III trials. In March 2019, researchers peeked at interim data whilethese trials — which were conducted in people with early-stage Alzheimer’s —were ongoing. They concluded that these were unlikely to succeed, and Biogenhalted both trials early.

But months later, the biotech firm broughtthe antibody back from the brink, after inspecting the data more closely. Theslow of cognitive decline was statistically significant in the subset ofparticipants who received the highest dose of aducanumab, Biogen’sre-analysis showed. Aducanumab did not have the same benefit when used at alower dose in this trial, and it didn’t show a benefit at any dose in the othertrial.

For Paul Aisen, director of the University of SouthernCalifornia’s Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute in San Diego, thetotality of the data supports approval. “My personal view is that aducanumab isan effective therapy,” says Aisen, whoconsults for Biogen.“But this was a problematic data set. It was a very fraught situation,” heconcedes.

These tensions were on display lastNovember at an FDA meeting to discuss the trial data. An independent panel ofexperts advising the FDA evaluated the data and argued strongly against Biogen’sassertion that the partial positive trial results carried more weight than didthe negative ones. Scott Emerson, a biostatistician at the University ofWashington in Seattle, who was on the panel, called the approach akin to“firing a shotgun at a barn and then painting a target around the bulletholes”.

The data also showed that aducanumab hasnon-negligible side effects. Around 40% of treated participants in the twotrials developed brain swelling. Most people wouldn’t have any symptoms relatedto the swelling, but they would need regular brain scans to avert dangerouscomplications — a burden for patients, neurologists and health-care systems.

At the November meeting, 10 out of 11 panellistsultimately voted that the presented data could not be considered as evidence ofaducanumab’seffectiveness; the remaining panellist wasuncertain. This week, the FDA reached the opposite conclusion.

Post-approval trial

As a condition of the FDA’s approval —which relied on the agency’s ‘accelerated approval’ programme — Biogen nowmust run a ‘post-marketing’ trial to confirm that the drug can improvecognition. It has yet to release details on when and how this trial will takeplace. Biogen hasup to nine years to complete the trial.

This worries industry watchers.“Experience shows that relying on accelerated approval to gather timely,high-quality post-approval evidence is not necessarily a given,” says Aaron Kesselheim, whostudies pharmacoeconomics atHarvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and is a member of the FDApanel that discussed aducanumab.

The FDA’s choice to grant acceleratedapproval to aducanumab — after a rollercoaster of a clinical-trial programme —could have broader implications, too. “This opens the door to drug companiesseeking to use the accelerated approval programme as a way of getting drugs on the marketbased on extremely low-quality evidence or post-hoc data fishing,” says Kesselheim.

Ripple effects

Biogen is now in line for a major windfall withaducanumab; its share price jumped by 40% on the approval.

Some experts had expected the FDA toapprove the antibody only for people with early-stage disease, but theregulator has not limited its use — anyone with Alzheimer’s can take it. Biogen willcharge around US$56,000 per year per person for the drug. If 5% of 6 millionpeople with Alzheimer’s in the United States receive the treatment, the drug’srevenue would reach nearly $17 billion per year. This would make it the secondtop-selling drug, by current revenues.

The Institute for Clinical and EconomicReview, a non-profit organization in Boston, Massachusetts, estimates that acost-effective price is $2,500–8,300 per year.

The approval is also likely to shake upthe development of future Alzheimer’s drugs, say researchers.

With a pathway to approval established,drug developers are likely to double down on anti-amyloid drugs. Drug companiesEli Lilly, Roche and Eisai already have anti-amyloid antibodies in phase IIItrials. They, too, might now be able to secure approvals with evidence ofamyloid-lowering activity, regardless of the compounds’ effects on cognition.

Before the approval, the researchcommunity had started to shift towards other drug targets associated withAlzheimer’s disease. For instance, more than ten drug candidates now inclinical trials are designed to clear another toxic protein from the brain,called tau.

David Knopman, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic inRochester, Minnesota, hopes that these and earlier-stage efforts won’t falteras a result of aducanumab’s win,based on amyloid-lowering activity. “We need to look at other targets,” he says.

The original text was published inthe news section of Nature on June 8, 2021

Author:Asher Mullard

EN

EN